Why the metaverse failed

I spent a decade freelancing for Hyper magazine. I wrote this back in 2016 just as augmented reality was starting to take off…

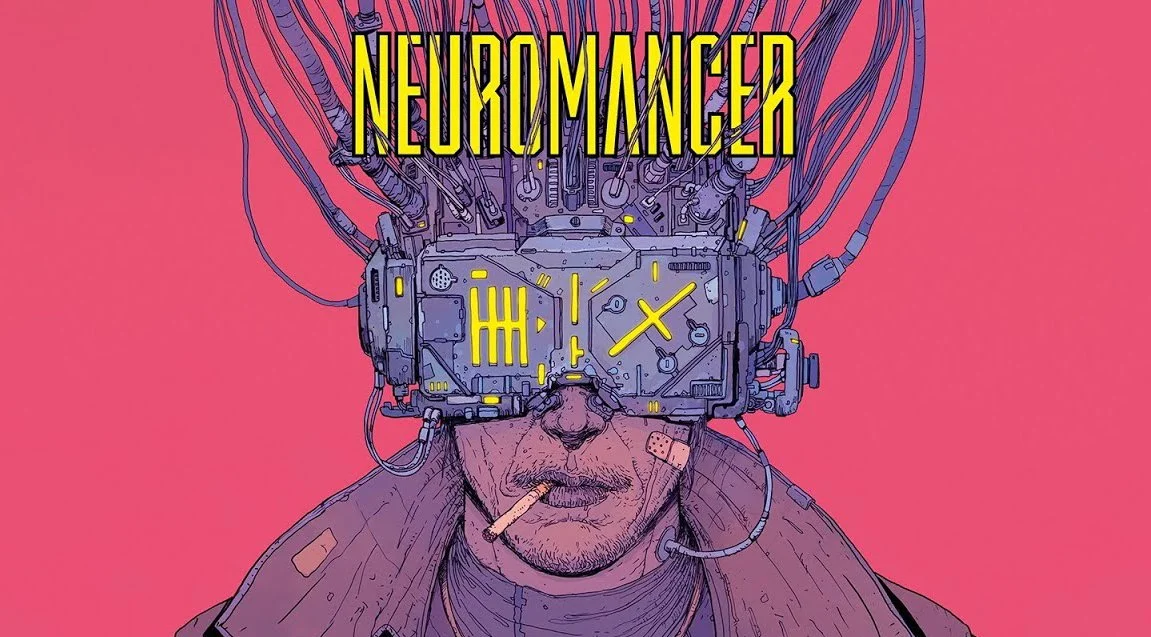

We’re first introduced to cyberspace and the concept of a new digital reality in William Gibson’s 1984 classic, Neuromancer. In the book, a cyber-hacker jacks into an online world known as the matrix via a series of nodes attached to his head.

As the text famously explains, “The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games. … Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts. … A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.”

Some 30 years later, our idea of alternate digital realities is still very much shaped by that initial idea. That someone has to physically connect with a peripheral to see and interact with these worlds. It’s the basis of the Oculus Rift and the new generation of VR Gear that’s getting rolled out for mass consumption.

But as William Gibson himself argued in a 2009 speech delivered at Vancouver Art Gallery, this fundamentally misses the point. We’ve already transcended the need for a bulky attachment strapped to our head. In 2016 we live inside an augmented reality that seamlessly connects the physical with the virtual; it’s just not the one we were promised.

Or as Gibson phrased it, “The physical union of human and machine, long dreaded and long anticipated, has been an accomplished fact for decades. We tend not to see it, because we are already it.”

Ch1.

In the original Matrix film, Neo has to access cyberspace with a crank shaft plunged into his nervous system. That imagery is straight out of Gibson’s Neuromancer, and it’s how many people view the eventually collision of real and virtual worlds.

As Gibson explains, “It’s easier to depict the union of human and machine literally, close up on the cranial jack please, than to describe the daily and largely invisible nature of an all encompassing embrace.”

In the past, this was all pretty self explanatory. After all, we inhabit the ‘real world’ and have the ability to access secondary, digital worlds via computers, or consoles, or suchlike. In the late ‘70s this may have meant a text based adventure on an Apple 2 computer, in the early 90s it was Mario running through the Donut Plains, and more recently it’s the Witcher 3 and vast open worlds.

But those distinctions are starting to blur, and an alternative theory has been offered, one that rejects this ‘digital dualism’ in favour of a unified whole. It argues that there’s no difference between atoms and bits. That they’re one and the same, and that they provide the framework of a brave new world.

In other words, we don’t need expensive VR headsets to experience alternative realities, we’ve already walking around inside them thanks to the intangible flow of data that emits form our phones, TVs, laptops, cars, and fancy refrigerators. We might not see it, and for the most part we choose to ignore I, but that doesn’t mean those invisible lines that connect people, places, and digital personas don’t exist.

Ch2.

Technology is funny. We get so caught up in the big-ticket items, the flying cars, moon colonies, and hoverboards, that we tend to miss the small incremental shifts that really change our lives.

No one held a party for the launch of university intranets, dial up modems, or early web browsers, but they provided the building blocks of the modern world.

As famed science fiction writer Bruce Sterling explains, this alternative cyberspace we’ve inadvertently constructed, is an extension of that same hazy timeline. It’s one that we only tend to see in retrospect, because the future, the real future, rarely arrives with a giant neon banner.

“Cyberspace is the ‘place’ where a telephone conversation appears to occur. Not inside your actual phone, the plastic device on your desk. Not inside the other person's phone, in some other city. The place between the phones. In the past twenty years, this electrical "space," which was once thin and dark and one-dimensional—little more than a narrow speaking-tube, stretching from phone to phone—has flung itself open like a gigantic jack-in-the-box. Light has flooded upon it, the eerie light of the glowing computer screen. This dark electric netherworld has become a vast flowering electronic landscape. Since the 1960s, the world of the telephone has cross-bred itself with computers and television, and though there is still no substance to cyberspace, nothing you can handle, it has a strange kind of physicality now. It makes good sense today to talk of cyberspace as a place all its own.” Bruce Sterling, Introduction to The Hacker Crackdown.

Ch3.

Mark Zuckerberg has a vested interest in Virtual reality, what with Facebook owning a significant stake in Oculus and all that. But speaking at the Facebook F8 conference in April 2016, he was already looking beyond the horizon, to the sort of world William Gibson and Bruce Sterling probably discuss over pints.

As Zuckerberg explained in his keynote, “Over the next 10 years, the form factor's just going to keep on getting smaller and smaller, and eventually we're going to have what looks like normal-looking glasses that can do both virtual and augmented reality. And augmented reality gives you the ability to see the world but also to be able to overlay digital objects on top of that.

“So that means that today, if I want to show my friends a photo, I pull out my phone and I have a small version of the photo. In the future, you'll be able to snap your fingers and pull out a photo and make it as big as you want, and with your AR glasses you'll be able to show it to people and they'll be able to see it.

“As a matter of act, when we get to this world, a lot of things that we think about as physical objects today, like a TV for displaying an image, will actually just be $1 apps in an AR app store. So it's going to take a long time to make this work. But this is the vision, and this is what we're trying to get to over the next 10 years.”

Mark Zuckerberg obviously doesn’t wear contacts, because his talk about AR/VR glasses is already quant when you throw digital lenses into the mix, but you the get the idea. Our worlds are colliding, and that distinction between the physical and the digital is slipping away much faster than many of us realise.

According to Gibson, it’s a journey that we started in the last century, as the Cold War propelled innovation and technology. “By the 1950s the human species was already in the process of growing itself an extended communal nervous system, and was doing things with it that had previously been impossible; viewing things at a distance, viewing things that had happened in the past, watching dead men talk and hearing their words… And the real marvel of this was how utterly we took it for granted.”

If you need evidence of all this just reach into your pocket. A century ago the features, apps, and power of your smartphone would have been considered witchcraft. Or at the very least something out of a distant future; one where we all lived on moon colonies and hang out with aliens at space ports like it wasn’t even a thing.

What we rarely stop to consider is all the algorithms, data, and infrastructure that allow our smartphones to play Pokemon Go, order an Uber, or tag a location, and how this all interacts with the physical world.

Pokémon GO found huge success by connecting the physical and the digital in a seamless fashion. It was probably the first time that Augmented Reality had ‘clicked’ with a mainstream audience. At the same time, it provided a fascinating insight into the complex, overlapping layers of data and information that envelope us.

Head into town on a Saturday afternoon and your average city streets is alive with social media posts, check-ins, geo-tags, blue tooth and Wi-Fi connections creating a web of data flow and digital worlds that we walk through with ignorant bliss.

This technology is only getting better and more integrated. Night Terrors, a new horror AR game currently in the works utilises all this data to map out users home, place ghosts within rooms, sent text messages, and measure heart rate while people explore their suddenly quite terrifying surroundings. It’s one of many games headed to market following the success of Pokemon Go.

Ch4.

This all brings us back to what’s real and what isn’t. And while that philosophical debate is beyond the scope of this article, the interconnection of man and machine, physical and digital, and the future evolution of games and entertainment allows us to give pause.

As Gibson stated in his Vancouver presentation, “The electrons streaming into a child’s eye from the screen of the wooden television are as physical as anything else.”

It’s a theory that’s further expanded by Nathan Jurgenson, who writes on Thesocietypages.org that, “We are not crossing in and out of separate digital and physical realities, ala The Matrix, but instead live in one reality, one that is augmented by atoms and bits. And our selves are not separated across these two spheres as some dualistic “first” and “second” self, but is instead an augmented self. A Haraway-like cyborg self comprised of a physical body as well as our digital Profile, acting in constant dialogue.”

Jurgenson argues that this relationship between our physical bodies and our digital lives is ever growing, strengthening, and firming. And that the actions we take in one are increasingly crossing over to the other. There’s plenty of evidence to back his claims.

Second Life offers players an abstract world to explore and build, but when real estate in the game began selling on EBay for hundreds of thousands of real world dollars back in the mid 2000s that divide between bits and atoms didn’t seem to account for much.

Sony’s failed experiment with Home might not have attracted the numbers it expected, but it’s advertising partnerships, and the ability for corporations to set up shop inside a digital world further eroded that line.

Then there’s World of Warcraft and the Chinese data mining farms it birthed. When real world factories are being set up to mine virtual goods to resell on the open market there’s an inertia that can’t be ignored.

As Sally A. Applin and Michael Fischer write in their paper, A Cultural Perspective on Mixed, Dual and Blended Reality, “The world has found a way to imbue itself within, around, underneath and on top of the Internet, and is indeed, currently in the process of expanding the Internet well beyond that which resides in machines.”

The Internet of things, which promises to connect everyday devices like toasters and fridges to an online network is already here, slowing meshing with our social media accounts, our smartphones, our geographic location.

All of this is much bigger, grander, more ambitious, and more fraught than

anything that has come before. It has the potential to fundamentally change both our world, and our place within it. But then it’s hard to see all this when you’re caught in the eye of the storm. And as Gibson reminds us, “The internet is a cybernetic organism. [And] the largest man made object on the planet.”

Ch5.

Deus EX: Mankind Divided has attracted media attention for taking contemporary issues about race and identity and projecting them into the future with its ‘Aug Lives Matter’ teasers. Go beyond the clickbait headlines, and the

game’s premise offers a fascinating take on the future, and what might happen if our phones and gadgets become part of our bodies as bolted on augments.

If that seems far fetched just think about the advances already being showcased at the Paralympics, or the fact we had artificial hearts being successfully inserted into patients as early as 1952.

This drive towards connection certainly hasn’t been smooth. Mostly recently, Google Glasses crashed and burned under a wave of poor product design, nerd shaming, and very real questions about privacy. But the push continues, and the once steadfast rules about what was comprises reality are being reconsidered as mobs of people scour city centres in search of virtual monsters, digital real estate continues to sell for real world cash, and Sega uses a virtual idol to pitch everything from hair care to …

It’s strange days indeed. And it’s only going to get stranger. Within that context the arrival of VR seems almost dated. Like a throwback to a simpler idea. Sure, it’s all very new, exciting, and immersive, but by it’s very nature it’s a walled environment. Something that requires a physical connection, a level of comfort and space. It’s a chance to explore new worlds, but it doesn’t fundamentally alter our world, or our place within it.

As Gibson notes, “Interface evolves towards transparency. The one you have to devote the least conscious effort to, survives, prospers. This is true for interface hardware as well, so the cranial jacks and brain inserts and bolts in the neck, all the transitional sci fi hardware of the sci fi cyborg already looks slightly quaint.”

Whether VR goes on to be the next big thing is still up for debate. But in the long term it may well be a footnote, or an evolutionary stopgap. Because the real leap forward game, the one that may define the next century, isn’t about visiting digital worlds, it’s about merging with them. And whether we realise it or not, we’re already barrelling down that road.

As Hideo Kojima recently stated in an interview with Edge Magazine. “It’s all coming together for AR right now: the technology, the market. It’s not something that is necessarily new, but it’s something that, thanks to the convergence of technology and access , is having its moment. I think everyone expected VR would come first and then AR would arrive much later. But it seems as though, against all those expectations, and with the help of cellphones, AR will come to dominate before VR even has a chance.”